Jar, attributed to the Keesee & Parr Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1861. Salt-glazed stoneware jar with cobalt decorations. H. 17 1/2". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Second view of the jar illustrated in fig. 1. Inscribed: “4” (four gallons). (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Third view of the jar illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Fourth view of the jar illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the decoration under the handle of the jar illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

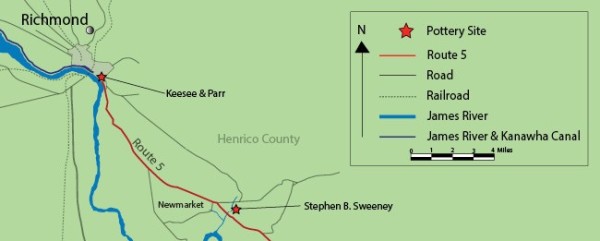

Map of the Richmond area of Virginia, showing the locations of the Keesee & Parr stoneware pottery and the Stephen S. Sweeney pottery.

Jar, Keesee & Parr Pottery, Richmond, Virginia, 1860–1865. Salt‑glazed stoneware. H. 14". Capacity: 3 gallons. Inscribed in cobalt: “Keesee & Parr / Richmond / Va” (Courtesy, The Valentine; photo, Crocker Farm Auctions.)

Churn, Fulton Pottery, Alleghany County, Virginia, 1867–1885. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Kurt Russ Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This four-gallon churn is decorated with a brushed blue-cobalt floral design and includes a centrally placed “palm” tree and signature.

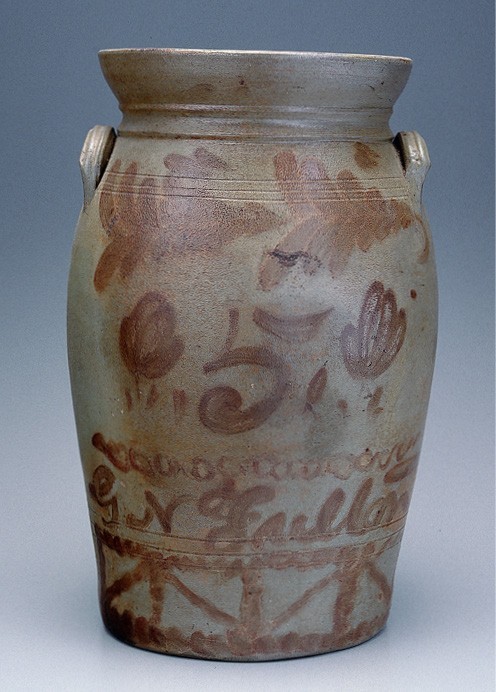

Churn, Fulton Pottery, Alleghany County, Virginia, 1867–1885. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/8”. (Kurt Russ Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) A five-gallon churn with a flaring rim, a well-defined collar, and applied crescent-shaped extruded handles exhibiting elaborate brushed manganese-dioxide decoration, including horizontally and vertically oriented floral motifs, a centrally placed “5” indicating vessel capacity, and the signature “G. N. Fulton” enclosed by horizontal wavy lines.

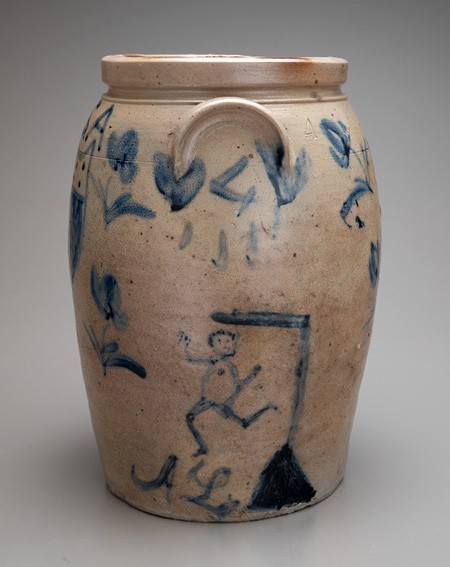

Storage jar, attributed to Stephen B. Sweeney, Henrico County, Virginia, 1838–1863. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 ½". (Private collection; photo, Kurt Russ.) The decorative motif on this one-gallon jar is a brushed-cobalt dancing man beneath one of the handles.

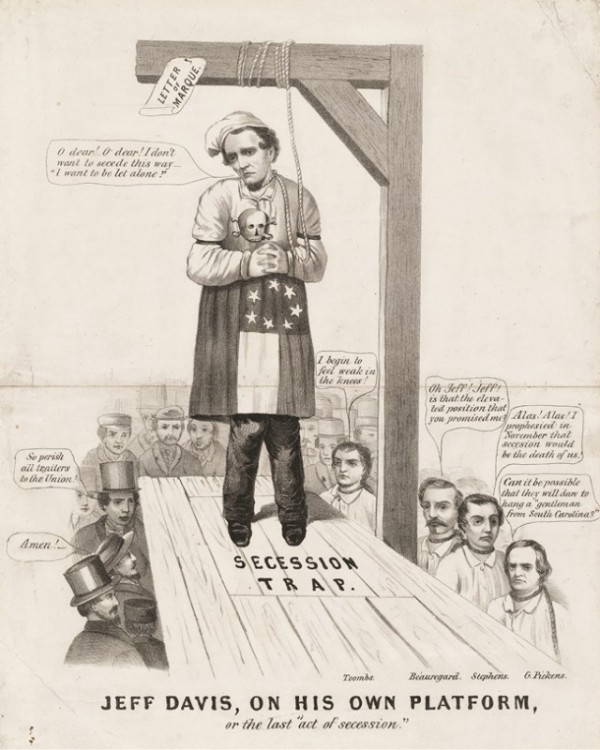

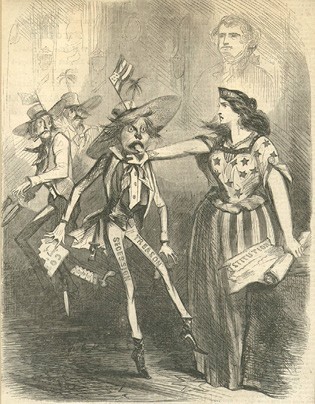

“JJEFF DAVIS, ON HIS OWN PLATFORM, or the last ‘act of secession.’ ” Currier & Ives, New York, ca. 1861. Lithograph on wove paper. 12 13/16” x 11". (Library of Congress.)

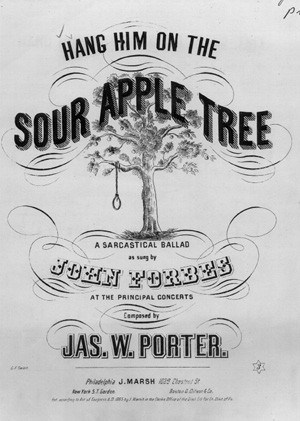

James W. Porter, Hang Him on the Sour Apple Tree, J. Marsh, Philadelphia, 1865. Notated music. (Library of Congress.) https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200001255/.

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 4.

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 2. Inscribed: “A L.” Note how the script of the letters is similar to those used on the signed Keesee & Parr jar illustrated in fig. 7.

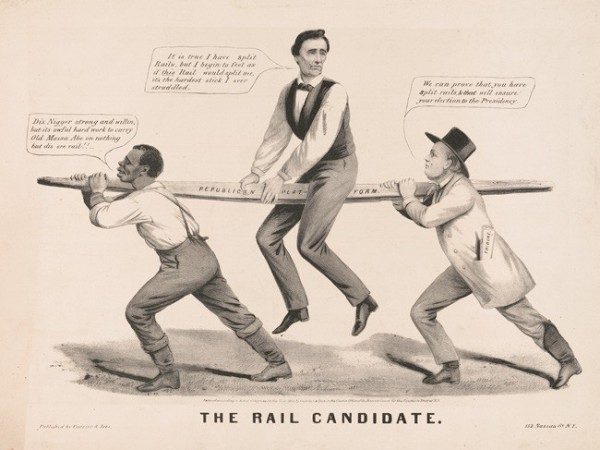

“The Rail Candidate,” Currier & Ives, New York, 1860. Lithograph. 10 5/8” x 14 1/8”. (Library of Congress.)

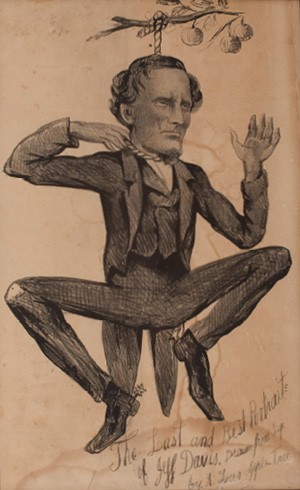

Jefferson Davis, undated. Drawing on paper. 10 ¼" x 16 ½". Handwritten inscription in lower right: “The Last and Best Portrait of Jeff Davis. Drawn from Life by A Sour Apple Tree.” (Heritage Auctions.) The drawing shows the president of the Confederate States struggling as he hangs from an apple tree.

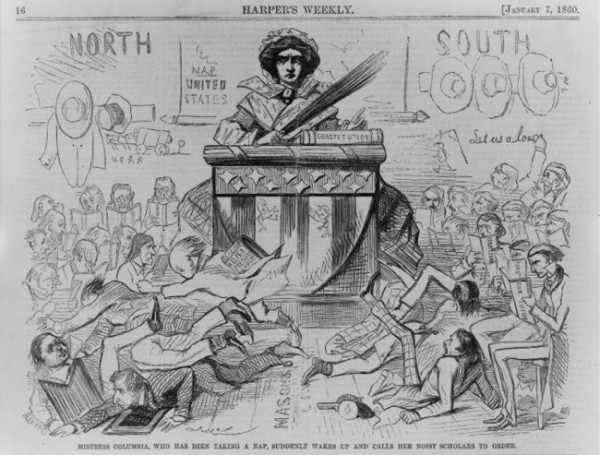

“Mistress Columbia,” Harper’s Weekly 4, no. 158 (January 7, 1860): 16. (Library of Congress.)

“Columbia Awake at Last,” Harper’s Weekly (June 8, 1861): 368. (Wikimedia Commons.)

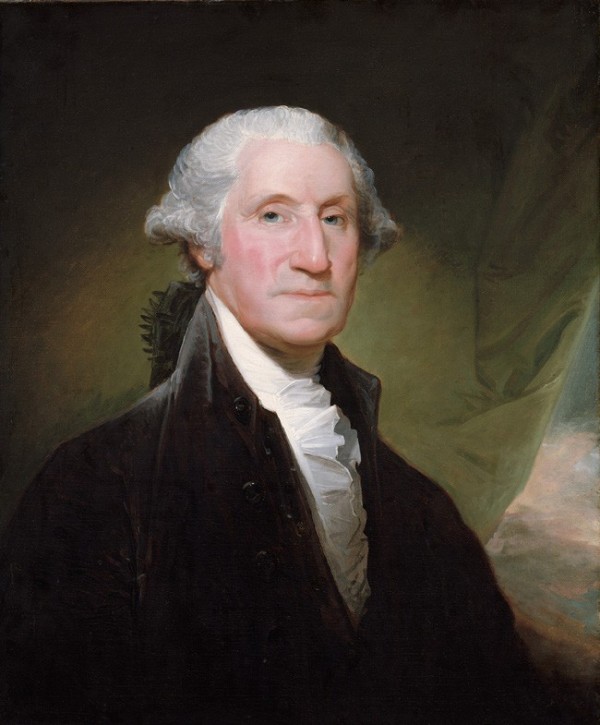

Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), George Washington, begun 1795. Oil on canvas. 30 ¼" x 25 ¼". (Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

NINETEENTH-CENTURY salt-glazed stoneware manufactured in the lower James River Valley has been collected and studied for more than half a century. Recent research has combined new archaeological information with intensive analysis of surviving pieces in public and private collections.[1] Although the vast majority of the stoneware products served utilitarian functions in both domestic and commercial contexts, a surprising number were decorated with well-developed pictorial statements, ranging in themes from comic to political. One such embellished example is a newly reattributed four-gallon salt-glazed stoneware jar from the Keesee & Parr pottery in Richmond, Virginia, that offers a rare glimpse into a perspective on the outbreak of the American Civil War.[2] Contrary to the sectionalistic or nationalistic political editorials that we often glean from the period, the jar’s cobalt decoration suggests that someone, either the decorator or a client, was decidedly displeased with all sides.

Viewed from one side, the jar looks like a paean to the Confederacy—it is marked “C.S.A.,” the initials for the Confederate States of America, and is decorated with a shield with three bars and eight stars, all surrounded with four tulip-like flowers (fig. 1). Turning the jar clockwise, the enthusiasm for Confederate victory becomes more violent, with a ghastly image of a figure hanging from gallows above the initials “A.L.” painted near the base (fig. 2). Coupled with the initials, the figure’s distinctly long, thin legs and hairstyle suggest that it represents Abraham Lincoln. The Confederate shield and Lincoln’s fate align, fitting into a growing iconography for the Confederacy. However, further turning the jar clockwise muddles the matter a bit.

Opposite the side showing the CSA shield is a different one, with stripes, also surrounded by four tulips (fig. 3). The word at the top of the shield has faded, probably during the firing process, but the beginnings of “Union” remain visible. Rotating the jar once more completes the confusing narrative, as now a different figure is shown hanging above the scrawled name “Jeff D…” (fig. 4). The key to comprehending the jar, we contend, lies in the face painted under the lug handle above this figure (fig. 5). Eyes narrowed and teeth bared, it conveys frustration, perhaps from the pressure to choose a side, and anger, directed equally toward the leaders of the Union and the Confederacy.

Although surprising, given Virginia’s outsize role during the Civil War, the divisiveness of political views in the commonwealth in this period suits both the jar’s attribution and its fractious decorations. Significantly, Virginia did not immediately secede from the United States along with South Carolina, and the highly charged discourse surrounding secession in the months leading up to its ultimate departure in April 1861 reveals the multiplicity of political views in the state at that moment in time. Few Virginians in the public sphere made arguments against white supremacy or the institutions of slavery, to be sure, but many fought against the idea of leaving the Union as the only means to preserve them.

In January 1861, a Richmond-area legislator warned his constituents about “disunionists” who wished to bring about secession, claiming that “This Union, which, if our internal dissensions can be allayed, is destined, in glory, in wealth, and in power, to outstrip all other Governments can be preserved, intact—can be maintained with equal rights to all the parties to it if Virginia will pursue a determined, but yet considerate course,” and presciently warning that “Disunion is a remedy for none of the ills Virginia has to deal with; its effect on her and the other border States would be particularly disastrous.”[3] Even as late as April 4, 1861, two-thirds of Virginia’s secession convention voted against a secession ordinance.

In addition to its reluctance to leave the United States, Virginia had a significant internal fissure with which to contend. Slavery’s central role in secession was not lost on contemporaries, pitting enslavers in the eastern regions of the commonwealth against westerners who were far less invested in it. Westerners resented the enslavers’ firm grip on political power, perceiving that it put them at far greater risk of harm than those in the east who were pushing for secession. As one assemblyman stated during deliberations over sending representatives to the secession conference in South Carolina in 1860, “It was useless to talk of secession without war. The Ohio river would be a blaze of fire in 30 days after the Union was dissolved, and he [Mr. Haymond, of Marion] thought he was as much interested . . . as gentlemen living far from what would be the seat of war.”[4] Ultimately, the events at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, brought about Virginia’s secession, but not as an intact state. The western portions seceded separately, and eventually formed West Virginia in 1863.

Reframing this stoneware jar within the particular context of political fracture in Virginia, the number of stars atop the Confederate States’ shield becomes especially meaningful. Unlike the official “stars and bars”—which first numbered seven, reflecting the initial states to secede, and then nine, after Virginia and North Carolina joined in the spring of 1861—this shield is topped by eight stars. That could have been a simple mistake on the decorator’s part, but the specificity of the remainder of the jar’s decoration suggests that the number is intentional. Eight stars would mark the occasion of Virginia’s entry into the Confederate States. The decorator’s violent treatment of both leaders also becomes more explicable given the context of the bombardment at Fort Sumter. To avoid appearing as an aggressor, President Abraham Lincoln sent supplies, not troops, in response to the requests for additional support by the fort’s leaders. The Confederate States’ newly elected President Jefferson Davis accurately believed that other slave states, especially Virginia, would secede from the Union and join the cause if war broke out, and he launched the attack on the fort that Lincoln anticipated. If decorator (or a client) of this jar were a politically astute pro-slavery Unionist, it would not be a stretch for them to conceive of Virginia’s position in the war as a tug-of-war between two treasonous gamblers deserving of identical fates.[5]

Richmond Stoneware

Regardless of the idiosyncrasies of Virginia’s secession-era politics, attributing the jar to a specific decorator in a particular Richmond pottery is something of a challenge, due to the numerous anonymous craftsmen working in these quasi-industrial firms. According to the U.S. Manufacturers’ Census for 1860, there were two “pottery ware” manufacturers in Henrico County: the Keesee & Parr stoneware pottery in the Rocketts neighborhood of Richmond, and Stephen B. Sweeney’s pottery on his farm in the eastern part of the county (fig. 6).

Each pottery was listed in the census as employing ten males.[6] At these potteries the men created utilitarian wares in substantial batches. Laborers could move from pottery to pottery, and worked in varying capacities. There is a distinct possibility that the individual who formed this jar on the wheel was not the one who created the lug handles, and it is highly likely that someone else applied the cobalt decorations.[7]

As seen with many of the potteries along the James River in the nineteenth century, the Keesee & Parr and Sweeney potteries’ stoneware objects share common stylistic characteristics, and discerning between the two can be difficult. Moreover, after Stephen B. Sweeney’s death in 1862, the entire property was sold at auction, where David Parr purchased many of the supplies and materials. Thus, stamps and other identifiers were used at both locations.[8] Further demonstrating the potential for exchange between the potteries, Watt Green, a free Black man who was listed in the 1850 census as working at Sweeney’s pottery, is listed in the 1869 Richmond city directory as an employee at the Keesee & Parr pottery.[9]

Some of the political perspectives of the “hands” at Richmond potteries can be ascertained from the activities that were documented in newspapers and other records. Many at the Keesee & Parr pottery were members of the David Parr family. Formerly a china dealer in Baltimore, David Parr relocated to Richmond around 1852, with the support of David Maulden Perine, a manufacturer of salt-glazed stoneware in Baltimore.[10] In 1857 Parr entered into a partnership with auctioneer Thomas Keesee, which lasted until 1862, when Parr brought his sons David Jr., John L., and James into the partnership (fig. 7).[11]

Although previous scholarship has suggested that the Parrs were Quakers and therefore pacifists and possibly abolitionists, contemporary accounts in newspapers suggest that by the mid-1850s the Parr family was deeply involved with the Methodist Episcopal Church in Rocketts.[12] They also were not opposed to the institution of slavery. In 1853 David Parr Sr. advertised that a man named Billy Holmes, whom he had rented from Captain Thomas Atkinson, had self-emancipated from his pottery at Rocketts, and Parr offered a reward for his return.[13] Furthermore, it appears that at least one of the Parr sons fought for the Confederate States, as David Parr Sr. placed an advertisement in Richmond papers, to be copied in national publications, requesting information about Private John L. Parr, taken prisoner at Front Royal, Virginia, on August 10, 1864.[14] However, Keesee & Parr employed potters of a range of political persuasions. Allowing for a little conjecture, it is easy to imagine a decorator or potter placing this jar in the kiln, anti-Confederacy images turned away from peers’ eyes, and hiding it among all of the other stacks of jars, churns, and chamber pots.

David Parr wrote on behalf of a Quaker man, Tilighman Vestal, who had been imprisoned in Richmond for objecting to his enlistment in the Confederate Army due to his pacifist beliefs; Vestal subsequently worked at the Keesee & Parr pottery for several years.[15] Joseph B. Ramey, another Richmond-area potter who may have worked for the Parrs, enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1862 and was injured in 1864.[16] Most important, Parr’s employees also included George Newman Fulton, an Ohio native who enlisted in the Union Army in 1862.

George N. Fulton was born in Loudoun County, Virginia, in 1834, but by 1835 the family had moved to Fultonham, Ohio, located in Muskingum County.[17] George learned his trade from his father, James Fulton, who was a local potter. During the 1850s George worked as a brick maker and bricklayer, but by 1856 he had moved to Richmond to work in the pottery shop of David Parr. There he is known to have made a massive twenty-gallon, salt-glazed beer or water cooler signed and dated “MAY 15 1856.” Fulton continued to work in the Parr shop until he enlisted as a private in the Union Army on July 23, 1862, with Company E of the 9th West Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment. In November 1864 he transferred to Company B of the 1st West Virginia Veteran Volunteer Infantry Regiment. A family tradition says that George Fulton was taken prisoner by Confederate forces at White Sulfur Springs, West Virginia.

After his discharge on June 14, 1865, Fulton eventually founded potteries on the western side of Virginia, first in Alleghany County, then possibly in Botetourt County. Extant works from these potteries are covered in elaborate, expressive brushwork decorations in cobalt and manganese, often helpfully paired with a very large signature (figs. 8, 9). We believe the brushwork on the Keesee & Parr workshop jar illustrated in figure 1 can be firmly attributed to Fulton, based on his Unionist views and his location in Richmond at the onset of the Civil War.[18]

It is worth noting that the Stephen B. Sweeney family, proprietors of the only other documented stoneware pottery in the Richmond area at the time, was more visibly dedicated to slavery and the Confederate cause than were the Parrs (fig. 10). Sweeney’s pottery was part of his larger farm operation; in the 1850 and 1860 census he is listed as a farmer and his son, Stephen Sweeney Jr., is noted as a farm manager in the 1860 census. Sweeney enslaved twenty-six people in 1850 and twenty-three people in 1860. While most probably labored on the farm, it is possible that some individuals labored in the pottery. Other individuals within Sweeney’s household are listed in these censuses as potters: the aforementioned Watt Green, as well as white potters Edward J. Clarke in 1850 and Patrick Murphy and another of Sweeney’s sons, Charles, in 1860.[19] Both Stephen Sweeney Jr. and Charles H. Sweeney served in the Confederate Army.[20] Because of its proximity to Bailey and Fourmile Creeks along the James River, the pottery was caught in the middle of several Union attempts to overtake Confederate troops and seize Richmond during the war.[21]

Reading the Jar

Any number of visual sources could have inspired the decorator’s imagery. The sardonic nature of the hanged figures correlates with the tone of contemporary political cartoons, which had become more abundant in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. The popularity of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, first published in 1855, accelerated regular publication of political cartoons in widely circulating media. Harper’s Weekly and Vanity Fair followed, in 1857.[22] The South added its own publication, Southern Punch, in 1860.[23]

Other popular prints, such as those by Currier & Ives, added to this plethora of visual culture and iconographic permutations in the years leading up to and during the Civil War. Hanging Jefferson Davis was a common theme in political cartoons from the beginning of the war. In a Currier & Ives print from 1861, Davis is draped in the “Stars and Bars,” standing on a platform at the gallows (fig. 11). Union soldiers sang about hanging Jefferson Davis from the old sour-apple tree from the beginning of the war, and this became another popular treatment of the Confederate president in contemporary media (fig. 12). In response, Confederate troops adapted the song with their own lyrics: “We’ll hang Abe Lincoln up a sower apple tree.”[24]

The depiction of Jefferson Davis on the jar is somewhat indistinct, perhaps due to firing or a tentative initial application (fig. 13), but Abraham Lincoln is easily recognized by his chin whiskers, even without the initials (fig. 14). Contemporary caricatures of Lincoln, including those that portray him in a positive light, exaggerate the tall statesman’s long legs. Likewise, the figure’s on the jar’s odd, splayed legs frequently were depicted in a similar manner in political cartoons. Further emphasizing his physique, the arrangement of his body echoes the numerous depictions of Lincoln riding a split rail that proliferated during his presidential candidacy (fig. 15). The hanging position of both presidents evokes dancing, with their arms and legs bent rather than limp, suggesting that the images are intended to be sarcastic and humorous (fig. 16).

The expression on the face painted under the jar’s handle is also found in contemporary political cartoons, especially those that depict “Miss Columbia,” a personification of the United States. In one, published in Harper’s Weekly in 1860, Miss Columbia is fashioned as a schoolteacher presiding over a rowdy classroom of misbehaving congressmen/students. Her large eyes are narrowed and angular, registering her frustration with representatives from the North and South alike (fig. 17). In another cartoon from Harper’s Weekly, published in 1861, Columbia has awoken and grasps a ghoulish figure, likely Jefferson Davis, by his neckerchief. Her face is arranged in the same firm-lipped, angered expression as before, but this time she stands in front of a portrait, likely of a founding father (fig. 18). Rather than mimicking Columbia, the decorator of the jar appears to have applied to a caricature of George Washington the typical conventions used to convey frustration and anger. The cobalt sweep over the handle terminates in slightly curved ends (see fig. 5), much like the curls of a powdered wig around a face (see figs. 4 and 19). The face’s toothy grimace implies clenched jaws, and references one of Washington’s most infamous features unseen in his portraits. He sees what is happening to the United States and is not pleased.

As much as this face alludes to George Washington’s anger at the state of his legacy, it also likely reflects the artist’s emotional state. Admittedly, without knowing precisely who the decorator or potter is or having any documentation of their attitude, or whether the piece was executed for a specific client, assigning a particular perspective or emotion to an artist is risky. However, no matter how humorous, the treatment assigned to Lincoln and Davis, as well as the conflicted nature of representing symbols of both sides in the Civil War, speaks to considerable frustration. If representative of the views of the decorator, George Washington becomes a proxy for the self. The Washington/decorator’s face therefore serves as a marker of bearing witness, of watching the country deteriorate into chaos and being unable to stop it.

Summary

As historian Michael E. Woods argues, Americans’ understanding of emotions leading up to and during the Civil War played a critical role in their comprehension of political events and decision-making processes. In many instances, emotions were cited as the common, bonding force for the country’s disparate groups. “Good feelings,” or “maintaining good feelings,” rather than political or national ties, allowed the states to remain joined together harmoniously. Disruptions to those good feelings, sparked by abolitionists in the North or fanned by secessionists in the South, would, in this framing, naturally dissolve those bonds.[25] Woods contends that various political groups played on the idea that emotional bonds could form communities and in turn encourage the creation of separate, sectional identities, essentially utilizing the discourse of emotion to amplify the key political and economic issues of the period.[26] Similarly, Kyle Osborn asserts that the kind of righteous anger and hatred of “the Yankee” encouraged by secessionists served as a unifying element for Southerners, who in actuality did not have much more of a singular “national” identity than did the rest of the United States.[27] Thus, the anger and frustration on display on the sides of the Richmond jar can be seen as twofold: partly at the leaders or groups that the decorator perceived as leading the country into war and chaos, and partly at the loss of an emotional community.

This stoneware storage jar, therefore, illuminates one of the forgotten paths that many Americans trod in the early stages of the Civil War: that of the unwilling participant. It offers an important reminder that, no matter our contemporary perspective and/or predominant tropes, the individuals who lived through major historical events often experienced them with much greater confusion than our hindsight affords. Rather than the black-and-white clarity of historians’ texts, the actual moment was, for many, a hopeless blur of blue and gray.

Kurt C. Russ, Robert Hunter, Oliver Mueller-Heubach, and Marshall Goodman, “The Remarkable 19th-Century Stoneware of Virginia’s Lower James River Valley,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), 200–258; Elizabeth J. Monroe, David W. Lewes, and Joe B. Jonas, “Preliminary Archaeological Assessment of a Waster Pit Associated with the Parr Pottery Works (44He0806), City of Richmond, Virginia” (Richmond: Virginia Department of Historic Resources, 2010).

Ex collection of Rex Stark, who purchased it from the Earl Rogers Jr. Collection at Skinner’s “Americana Auction,” March 24, 1983, lot 95; acquired for the William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation. The jar was the subject of study for the senior author and discussed at the MESDA Summer Institute Final Presentations, July 16, 2021, sponsored by a William C. and Susan S. Mariner Southern Ceramics Fellowship.

Wms. C. Wickham, “The State Convention,” Richmond Dispatch, Thursday, January 17, 1861, p. 2.

“House of Delegates, Thursday, January 27,” Richmond Dispatch, January 28, 1860, p. 1.

Michael E. Woods, “Secession and Disunion,” in The Cambridge History of the American Civil War, edited by Aaron Sheehan-Dean, 3 vols. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 2:44–45, 56, 59–61.

United States Census of Manufactures, Virginia State Table, 1860, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1865/dec/1860c.html (accessed July 2, 2021); “Stephen B. Sweeney” and “Keesee & Parr,” United States Census of Manufactures, 1860, Eastern District, Henrico, Virginia, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/1276/images/T1132_8-00510?ssrc=&backlabel=Return&pId=3060096 (accessed July 12, 2021).

Oliver Mueller-Heubach, “From Kaolin to Claymount: Landscapes of the 19th-Century James River Stoneware Industry,” Ph.D. diss., College of William & Mary, 2013, pp. 244, 248–50.

Russ et al., “Remarkable 19th-Century Stoneware of Virginia’s Lower James River Valley,” p. 233.

Richmond City Directory, 1869, U.S. City Directories, 1822–1995, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/690102648:2469?tid=&pid=&queryId=8649be444c1116924f90d74ff7d32d91&_phsrc=iDw2&_phstart=successSource.

Advertisement, Richmond Dispatch, April 27, 1852, p. 2.

Advertisement, Richmond Dispatch, October 10, 1862, p. 4; Mueller-Heubach, “From Kaolin to Claymount,” pp. 112–13.

Advertisement, Richmond Dispatch, July 1, 1857, p. 2; advertisement, Richmond Times, November 13, 1866, p. 3; “Notes,” Richmond Times, April 11, 1867, p. 4. On the history of the Methodist Episcopal Church in Rocketts, “Notes” credits David Parr as the first superintendent of the Rocketts Sunday School.

Advertisement, Richmond Dispatch, September 12, 1853, p. 3.

Advertisement, Richmond Enquirer, September 13, 1864, p. 3.

Russ et al., “Remarkable 19th-Century Stoneware of Virginia’s Lower James River Valley,” p. 212.

“Joseph B. Ramey,” Historical Data Systems, Duxbury, Mass., American Civil War Research Database, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/321599:1555?tid=&pid=&queryId=71bc28726b9e5d8aa740e46d4609db0a&_phsrc=zKE6&_phstart=successSource (accessed July 12, 2021).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_N._Fulton.

Kurt C. Russ, “The Remarkable Stoneware of George N. Fulton, circa 1856–1894,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 158, 162–73.

United States Federal Census, 1850, Henrico, Virginia, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8054/images/4206372_00527?usePUB=true&_phsrc=loA2&_phstart

=successSource&usePUBJs=true&pId=15152057 (accessed July 12, 2021); United States Federal Census, 1860, Eastern Division, Henrico, Virginia, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/34299168:7667?tid=&pid=&queryId=e647649feb2377019b8c3d81fa8d01b5&_phsrc=eJx1&_phstart=successSource (accessed July 12, 2021).

“Charles H. Sweeney,” National Park Service, United States, Civil War Soldiers, 1861–1865, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/5329831:1138?tid=&pid=&queryId=a091244d0430c44a68074bfc3615adf6&_phsrc=qrt3&_phstart=successSource (accessed July 12, 2021); “Stephen B. Sweeney,” Historical Data Systems, Inc., Duxbury, Mass., American Civil War Research Database, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/2371885:1555?tid=&pid=&queryId=f64cb8061f92017e21d8801db5bc3b54&_phsrc=qrt6&_phstart=successSource (accessed July 12, 2021).

Mueller-Heubach, “From Kaolin to Claymount,” pp. 108–9.

J. G. Lewin and P. J. Huff, Lines of Contention: Political Cartoons of the Civil War (New York: Collins, 2007), p. x.

Kristen M. Smith, ed., The Lines Are Drawn: Political Cartoons of the Civil War (Athens, Ga.: Hill Street Press, 1999), p. xv.

See Heritage Auctions, “Civil War-Era Manuscripts, Poems, and Letters,” December 12, 2015, lot 47213. A version of the song is included in Marty Duncan’s A Civil War Romance (Pittsburgh, Pa.: Red Lead Press, 2011), p. 49.

Michael E. Woods, Emotional and Sectional Conflict in the Antebellum United States (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), pp. 25–28.

Ibid., pp. 29–31.

Kyle N. Osborn, “An Emotional Rebellion: Wrecking the Old South’s Emotional Community,” in Southern Communities: Identity, Conflict, and Memory in the American South, edited by Steven E. Nash and Bruce E. Stewart (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019), p. 82.